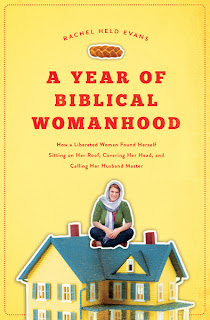

The first book I read in 2013 was A Year of Biblical Womanhood by Rachel Held Evans. Below is the first paragraph from the description on the back of the book.

Strong-willed and independent, Rachel Held Evans couldn’t sew a button on a blouse before she embarked on a radical life experiment—a year of biblical womanhood. Intrigued by the traditionalist resurgence that led many of her friends to abandon their careers to assume traditional gender roles in the home, Evans decides to try it for herself, vowing to take all of the Bible’s instructions for women as literally as possible for a year.She emphasizes a virtue each month, roughly corresponding to the Jewish year by beginning in October and ending in September. So, each month is basically a chapter. Some of the virtues are simply Christian virtues that anyone should strive for, no matter their gender, for example gentleness, valor, justice, grace. Other virtues are typically thought of as primarily feminine, for example domesticity, beauty, modesty, silence.

Between the months, she explores a woman of the Bible. I particularly enjoyed these interludes. Of course, she writes about the obvious women like Mary the mother of Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Ruth. Those are women who have been revered and celebrated by many. However, she also courageously explores women of the Bible who have been mostly neglected or overshadowed by other characters in their story, like Tamar (the daughter-in-law of Judah), Vashti, and Leah.

Likely, the first question a Christian will ask when reading this book is, "Why is she doing all of these Old Testament things?" Do not make the mistake of assuming that Evans is making a hermeneutical error here. She is exploring Biblical womanhood, and the Old Testament is part of the Bible. Though I haven't read AJ Jacobs' The Year of Living Biblically, I gather that her attempt is similar in scope. She corresponds with a Jewish lady for help in understanding and carrying out many of the Old Testament traditions. She travels to Pennsylvania to converse with Amish and Mennonite women about modesty. She visits a monastery in Alabama to explore silence and prayer. She considers what both Testaments say about women and how people have interpreted and applied those things.

This book is partly about complementarianism versus egalitarianism and partly about hermeneutics. It is obvious that Evans is at odds with the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, and I can't say that I blame her. She is egalitarian in her view and makes a good biblical case for her view. But there is no doubt that one's hermeneutics will influence whether one is complementarian or egalitarian.

Practically, though, (This is my opinion; I don't recall Evans stating this.) modern American marriages are egalitarian. Even the staunchest complementarians I know, the ones who remind me often of 1 Peter 3:1-6 and Ephesians 5:22, those men ask permission before going hunting, playing golf, or whatever else they do to hang out with the guys. They also do dishes, laundry, cook, and change diapers. I'm not saying they're not Biblical men and I'm not saying there is anything wrong with a man doing household chores. I'm just saying that I once claimed to be a staunch complementarian and I asked permission, did all those household chores, and I never once overruled my wife. The same is true, to the best of my knowledge, of almost every other "complementarian" husband I know. So, practically, complementarianism seems non-existent in modern American marriages anyway, even among complementarians. What's wrong with admitting it? Evans builds a good case for an egalitarian marriage.

Regarding the roles in the church, complementarianism versus egalitarianism makes more practical sense in America. I know plenty of churches that won't allow women even so much as to announce to the congregation that her child is sick and her husband is home with the sick child (another example of the prevalence of egalitarian marriages among so-called complementarians). Most conservative evangelical churches will not allow women to be pastors. Many will not allow women to be deacons or evangelists, either. There are some that won't allow women to teach a Bible class if men are present. Again, hermeneutics come into play here. The staunchest complementarians have some problems, namely Priscilla, the praying and prophesying women in 1 Corinthians 11, Junia the apostle, Phoebe the deacon, and others. The boldest egalitarians have some problems, namely Paul. Especially troubling to egalitarians are his instructions to Timothy that women are not to have authority over men.

Evans does an admirable job of dealing with the complementarian proof texts and she does a very good job of establishing that the Bible teaches egalitarian principles as the ideal. Still, though, some of her explanations of the complementarian texts were as uncomfortable as the complementarians fidgeting over Junia and female prophets and Deborah.

Again, it comes back to hermeneutics. She has some brilliant nuggets about hermeneutics, and this is where the book shines. Though it's (thankfully) not a book about hermeneutics (that wouldn't have sold nearly as well), the hermeneutic lessons she shares are very good. Allow me to quote some that stood out to me.

The Bible isn’t an answer book. It isn’t a self-help manual. It isn’t a flat, perspicuous list of rules and regulations that we can interpret objectively and apply unilaterally to our lives.The following one I think describes Evans and the "Biblical manhood and womanhood" crowd and many people I know and even me.

When we turn the Bible into an adjective and stick it in front of another loaded word (like manhood, womanhood, politics, economics, marriage, and even equality), we tend to ignore or downplay the parts of the Bible that don’t fit our tastes... More often than not, we end up more committed to what we want the Bible to say than what it actually says.Still more good stuff on hermeneutics.

[T]he notion that [the Bible] contains a sort of one-size-fits-all formula for how to be a woman of faith is a myth... If love was Jesus’ definition of “biblical,” then perhaps it should be mine.She astutely points out this dirty little hermeneutical truth that nobody wants to admit.

For those who count the Bible as sacred, interpretation is not a matter of whether to pick and choose, but how to pick and choose. We are all selective.

And after going through some examples that prove the truth that you can find whatever you're looking for in the Bible, she summarizes with this gem.

Are we reading with the prejudice of love or are we reading with the prejudices of judgment and power, self-interest and greed?

All in all, I highly recommend this book. If you want to be comfortable and continue to ignore some of the things in the Bible that don't fit what you want the Bible to say, don't read it. If you want to pick her apart and bash her project and call her Satan's helper, you'll certainly find cause to do that. Others have. Don't expect to agree with all her conclusions and methods and language. But I think this book is witty and challenging and well written. I definitely give it a thumbs up. Even where I disagree with her, I respect her approach.